Corea. Una historia paralela

( Corea. A Parallel Story ) — 2015 / 17

![]()

Sinopsis

En la primera mitad de la década de 1950 se producen en España dos acontecimientos de resonancia asimétrica en la historia. El primero de ellos, la firma de los acuerdos bilaterales con los Estados Unidos, los Pactos de Madrid de 1953, que en pleno auge de la guerra fría condicionarán el desarrollo posterior de la política española, durante y tras la dictadura, al menos hasta el definitivo ingreso en la OTAN en 1986. El segundo emerge a la sombra del primero como una anécdota que, en apariencia, carece de significado histórico. Por todo el Estado se están inaugurando proyectos de urbanización marginal, viviendas sociales que apenas serán capaces de contener la llegada a las ciudades de los que abandonan el campo o los que, sencillamente, se apiñan en casas insalubres. Recibirán el nombre del dictador (Barriada de Francisco Franco, Grupo Generalísimo Franco) o el de una virgen (La del Perpetuo Socorro, La Inmaculada), pero no tardarán en ser reconocidos por otro nombre, el de la guerra contra el comunismo que libra, en el confín del mundo, el amigo americano: “Corea”.

Diseminados por el territorio (Huesca, La Coruña, León, Toledo, Palencia o Palma de Mallorca), los barrios de “Corea” conformarán un archipiélago de sospecha y miedo. En su función institucionalizada demarcarán el umbral entre la pertenencia socialmente aceptable y su afuera. Ser “coreanos” significará existir en el límite social. Sujetos por el insulto, sujetos por la violencia nominativa que se inscribe en los cuerpos y los pone en su lugar. En un vaivén perverso entra la inclusión y la exclusión: lo mismo víctimas de la miseria y la ignorancia, que amenaza para el imperio del orden moral dominante. El nombre de “Corea” va a inaugurar un infrasujeto cuya abyección y estigma han perdurado en el tiempo, atravesando la historia reciente del país.

Abstract

Two events of asymmetric historic relevance took place in Spain in the first half of the 1950s. First, the signing of the Bilateral Agreement for Mutual Defense with the USA, the Pact of Madrid of 1953, signed during the rise of the Cold War. It shaped the development of Spanish politics, during and after the dictatorship, to a certain degree, until the country attained NATO membership in 1986. The second event materialized as a historically insignificant anecdote, in the shade of the first. All over the nation, marginal urbanisation projects opened, social housing that could barely contain the massive flood of people leaving the countryside for the cities or those who huddle simply in unsanitary homes. They were named after the dictator (Francisco Franco) or a Virgin (La del Perpetuo Socorro, La Inmaculada) but it did not take long before they were known by a different name, taking that of the war against communism led by the American friend half-way around the world: “Corea”.

Scattered over the Spanish territory (Huesca, La Coruña, León, Toledo, Palencia o Palma de Mallorca), the “Corea” neighbourhoods form an archipielago of suspicion and fear. Their institutional role demarcates the threshold between socially acceptable belonging and the outside of it. To be “coreanos” means to exist on the edge of the social. Subjects in insult, subject to a nominal violence that inscribes the bodies and puts then in their place. A perverse to and fro from inclusion to exclusion: both victims of misery and ignorance and threat to the rule of a dominant moral order. The name “Corea” inaugurates an infra-subject whose abjection and stigma have endured in recent Spanish history.

Grupo de viviendas del 25 de Marzo (nombrado en conmemoración de día de la Ofensiva Final del bando sublevado durante la Guerra Civil), "Corea". Barrio del Perpetuo Socorro, Huesca.

25 de Marzo housing estate (named after the date of the final offensive by the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War: March 25, 1939), “Corea”. Perpetuo Socorro neighbourhood, Huesca.

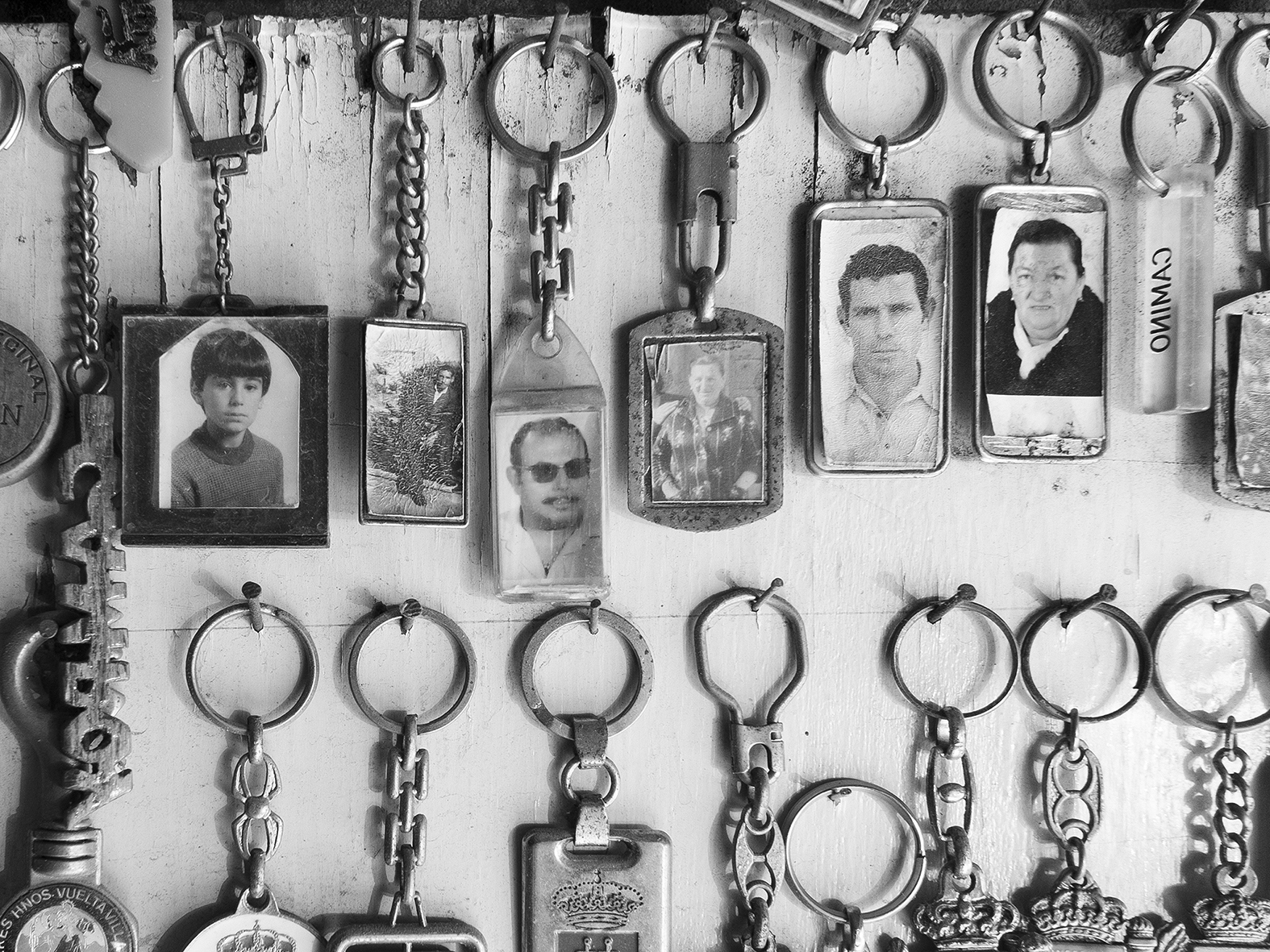

Retratos de la familia Campoy como parte de una colección de llaveros emprendida por uno de sus miembros. Domicilio particular. Inmediaciones de "Corea". Barriada de la Asunción, León.

Portraits of the Campoy family as part of a key-ring collection organised by a member of the family. Private home. In the vicinity of “Corea”. La Asunción neighbourhood, León.

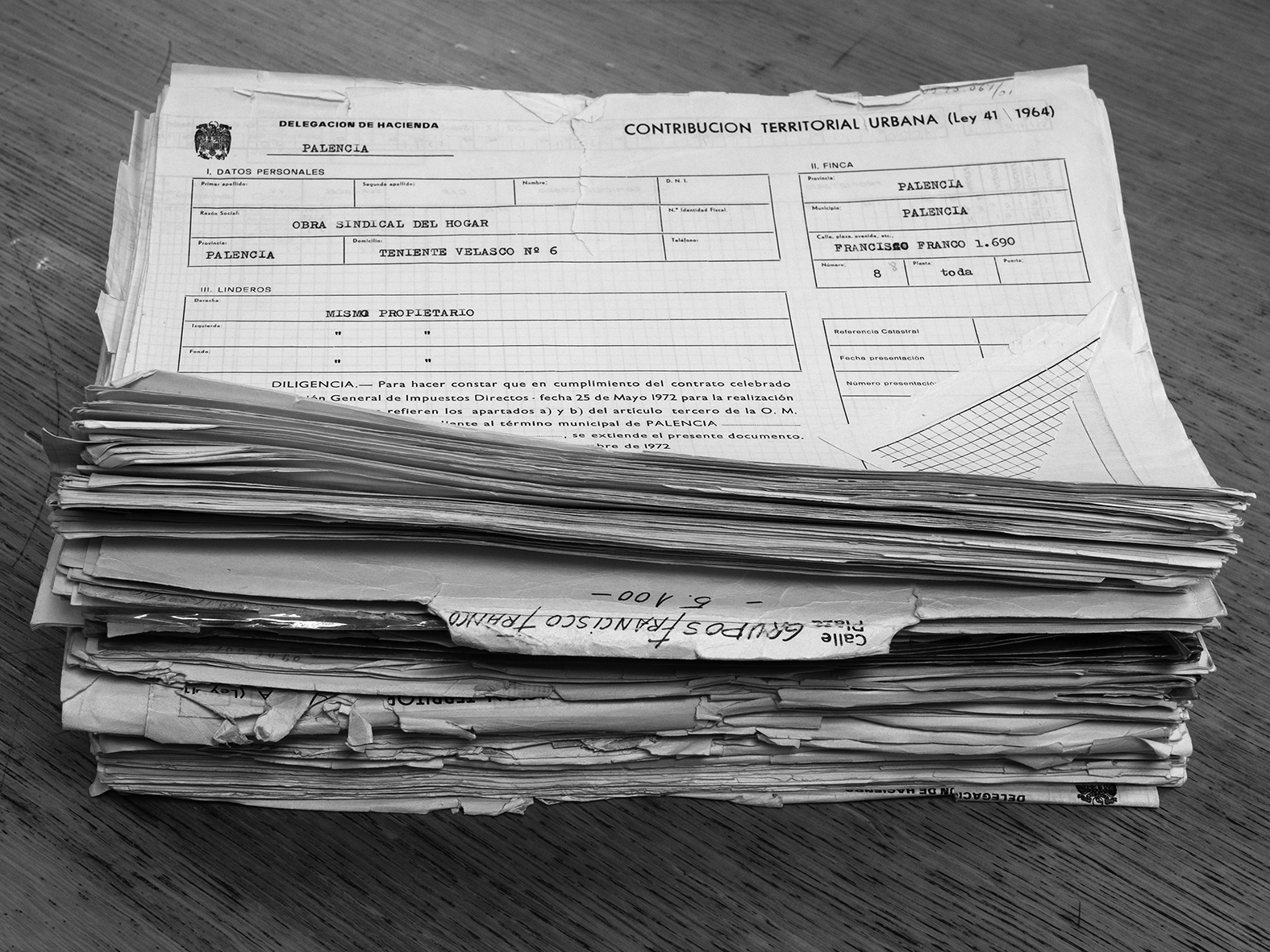

Documentación catastral del grupo de viviendas Francisco Franco, barriada de «Corea». Única documentación conservada sobre el barrio en el Archivo Histórico Provincial de Palencia.

Land registry documents for the Francisco Franco housing estate, “Corea”. The only documents about the neighbourhood still kept in the Provincial Historic Archive of Palencia.

Palencia,

18 de diciembre de 1955

Palencia, 18 de diciembre de 1955

( Palencia. December 18, 1955 )

Domingo. 10:30 h de la mañana. Barriada de Francisco Franco,

«Corea».

Concluidas, tras cuatro años

de trabajos, las obras de edificación, tiene lugar, al otro lado de las vías,

el acto de entrega de llaves a los beneficiarios. Hasta allí se han desplazado

esta mañana, dejando la comodidad del centro de la ciudad, el Ayuntamiento en

pleno, las autoridades sindicales, y algunos empresarios y promotores

involucrados. Los actos religiosos oficiados, en esta ocasión, por el obispo de

la diócesis, José Souto Vizoso, inauguran la jornada. Día festivo en la plaza

del Generalísimo. Misa de campaña, panegírico del Bautista y bendición de las

casas. Premio a la gracia del mejor peinado, al más valioso mantón de Manila.

Beso a la reliquia, ramas de tomillo del monte y orquesta, y chotis danzón, y

niños pedigüeños con platillo y estampa de Santa Rita. ¡Una perra pa’ San

Juanillo!

La Obra Sindical del Hogar brinda cuatro becerras que morirán a estoque por productores del gremio y sus cuadrillas, cinco flamantes bicicletas y, al productor que demuestre mayor antigüedad en la misma empresa, trescientas pesetas; trescientas para el que lleve mayor número de años afiliado al Sindicato de la Construcción y al del Vidrio y Cerámica; trescientas al que tenga mayor número de hijos vivos menores de catorce años; trescientas al trabajador fijo más antiguo en cualquier grupo de producción con mayor número de hijos trabajando para empresas encuadradas en esa rama sindical; trescientas al más veterano en activo; doscientas canjeables por productos en comercios de la capital para los diez que sean agraciados por sorteo; cincuenta para veinte afortunados al azar.

(...) Un total de 628 familias acceden a las nuevas viviendas, la mayoría provenientes del éxodo rural. Algunas de estas personas se ven obligadas, para calentarse en invierno, a recoger clandestinamente el carbón caído en las vías del tren. Su situación de carestía les obliga también, en muchas ocasiones, a recurrir al Auxilio Social de la Sección Femenina y a las parroquias donde se reparte, desde el convenio bilateral con Estados Unidos en 1953, leche en polvo y galletas.

La Obra Sindical del Hogar brinda cuatro becerras que morirán a estoque por productores del gremio y sus cuadrillas, cinco flamantes bicicletas y, al productor que demuestre mayor antigüedad en la misma empresa, trescientas pesetas; trescientas para el que lleve mayor número de años afiliado al Sindicato de la Construcción y al del Vidrio y Cerámica; trescientas al que tenga mayor número de hijos vivos menores de catorce años; trescientas al trabajador fijo más antiguo en cualquier grupo de producción con mayor número de hijos trabajando para empresas encuadradas en esa rama sindical; trescientas al más veterano en activo; doscientas canjeables por productos en comercios de la capital para los diez que sean agraciados por sorteo; cincuenta para veinte afortunados al azar.

(...) Un total de 628 familias acceden a las nuevas viviendas, la mayoría provenientes del éxodo rural. Algunas de estas personas se ven obligadas, para calentarse en invierno, a recoger clandestinamente el carbón caído en las vías del tren. Su situación de carestía les obliga también, en muchas ocasiones, a recurrir al Auxilio Social de la Sección Femenina y a las parroquias donde se reparte, desde el convenio bilateral con Estados Unidos en 1953, leche en polvo y galletas.

Sunday. 10.30 in the morning. Francisco Franco neighbourhood, “Corea”. After four years’ work, the building

is finished and it is time for the ceremony of handing over the keys to the

recipients on the other side of the track. All members of the City Council, the

union representatives and some business owners and developers who have been

involved have all come out here this morning, leaving the comfort of the city

centre. The religious ceremony officiated today by the Bishop of the diocese,

José Souto Vizoso, starts the proceedings. A feast day in the Plaza del

Generalísimo. Open-air mass, eulogy of St John the Baptist and blessing the

homes. A prize for the best hair-do, for the most beautiful Manila shawl.

Kissing the relic, bunches of wild thyme and dancing the chotis and kids scrounging with a collection plate and picture cards

of Santa Rita. A copper for San Juanillo!

The Obra Sindical del Hogar 1 provides four bull calves that will die in a bullfight at the hand of guild members and their squad, five shiny new bicycles and three hundred pesetas for the producer who has been longest in the same company; plus three hundred for whoever has been the longest serving member in the Building Union and Glass and Ceramic Union; three hundred for whoever has the most living children under fourteen years old; three hundred to the oldest permanent worker in any production group with the most children working for firms in the same Union branch; three hundred to the oldest person still working; two hundred to spend on products in local businesses for ten raffle winners; fifty for twenty lucky ones.

(...) A total of 628 families have access to the new homes, most of them coming from the rural exodus. Some of these people find themselves obliged to secretly collect coal fallen on the railway tracks to keep warm in the winter. Their precarious situation means they often have to resort to Social Aid from the Sección Femenina and to the parish church where since the bilateral agreement with the United States in 1953, powdered milk and biscuits are handed out.

1. Falangist Union for Home Welfare

The Obra Sindical del Hogar 1 provides four bull calves that will die in a bullfight at the hand of guild members and their squad, five shiny new bicycles and three hundred pesetas for the producer who has been longest in the same company; plus three hundred for whoever has been the longest serving member in the Building Union and Glass and Ceramic Union; three hundred for whoever has the most living children under fourteen years old; three hundred to the oldest permanent worker in any production group with the most children working for firms in the same Union branch; three hundred to the oldest person still working; two hundred to spend on products in local businesses for ten raffle winners; fifty for twenty lucky ones.

(...) A total of 628 families have access to the new homes, most of them coming from the rural exodus. Some of these people find themselves obliged to secretly collect coal fallen on the railway tracks to keep warm in the winter. Their precarious situation means they often have to resort to Social Aid from the Sección Femenina and to the parish church where since the bilateral agreement with the United States in 1953, powdered milk and biscuits are handed out.

1. Falangist Union for Home Welfare

Sala de ocio compartido en el local de la asociación de vecinos. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Barrio del Perpetuo Socorro. Huesca.

Communal recreation room in the premises of the residents’ association. In the vicinity of “Corea”. Perpetuo Socorro neighbourhood, Huesca.

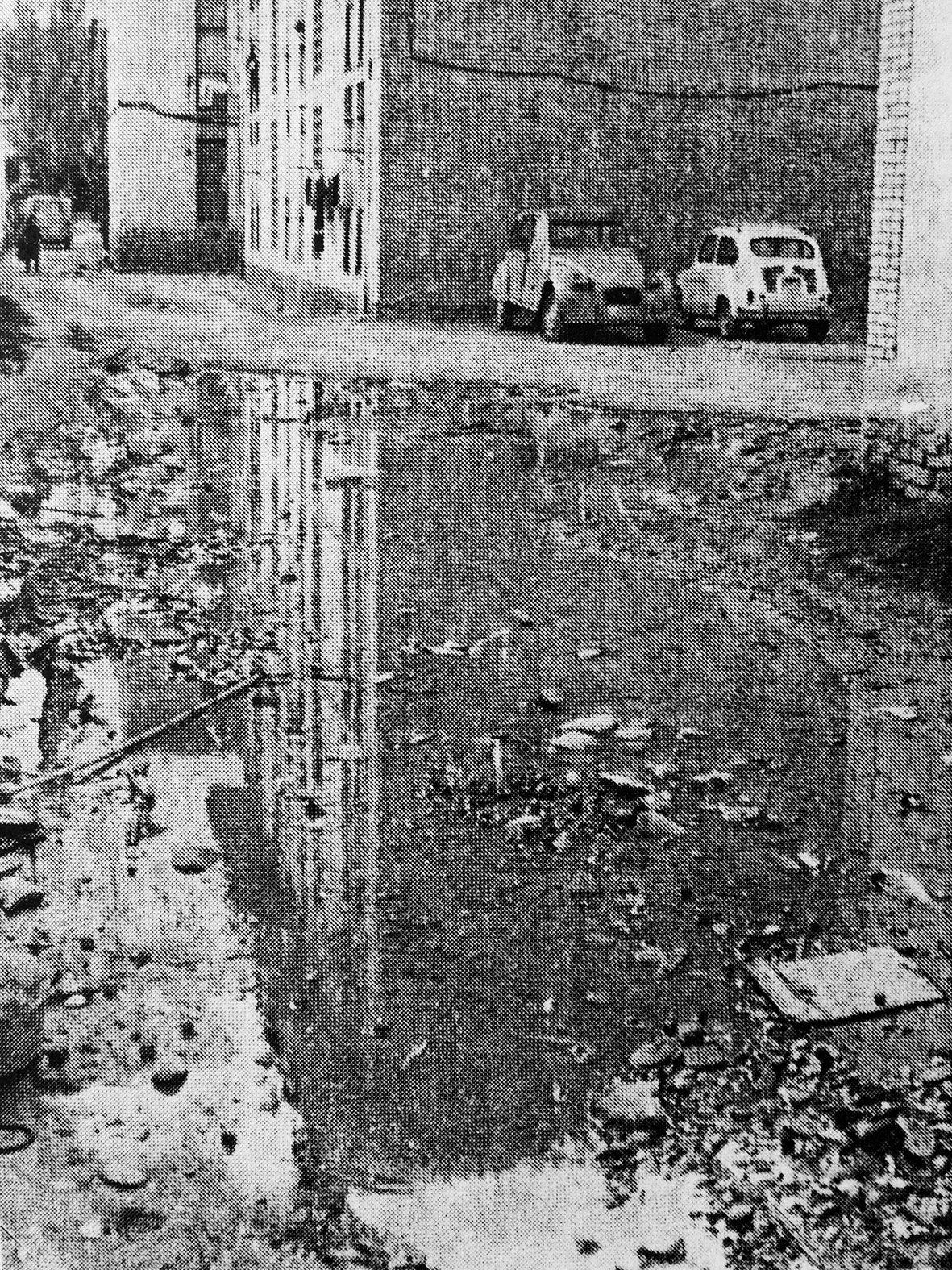

Vista de una calle en el barrio del Cristo del Otero. Palencia.

View of a Street in the Cristo del Otero neighbourhood, Palencia.

Recogiendo agua en la fuente del barrio. Archivo de la Parroquia de la Inmaculada, «Corea», León.

Collecting water from the neighbourhood's pump. Archive of the La Inmaculada's Parish. "Corea". León.

Collecting water from the neighbourhood's pump. Archive of the La Inmaculada's Parish. "Corea". León.

El hospital de León visto desde la barriada de La Inmaculada, "Corea".

The León Hospital seen from La Inmaculada neighbourhood, "Corea".

León, 18 de julio de 1952

León, 18 de julio de 1952

( León. July 18, 1952 )

Día de la conmemoración del decimosexto aniversario del Alzamiento Nacional. (...) Hasta 108 familias numerosas y de bajo nivel de renta disfrutarán de las Casas del Aguinaldo. Estas se han levantado sobre el viejo asentamiento informal que desde principios de siglo habían construido los trabajadores de las pequeñas fábricas cerámicas que proliferaban en la zona. Las Casas del Aguinaldo no cuentan con agua corriente ni alcantarillado; tampoco con instalaciones sanitarias. Debido a la cualidad arcillosa del suelo y a la falta de urbanización, los días de lluvia las calles polvorientas se convierten en lodazales. La superficie total de las viviendas, que cuentan con tres habitaciones y patio, no alcanza los 100 m2. Algunas familias deben convivir con cinco o seis hijos, pues la densidad de población es elevada. La barriada no cuenta con ningún tipo de abastecimiento ni conexión con la ciudad. En su mayoría, los habitantes provienen de zonas rurales en el interior. La barriada no tardará en ser reconocida como «Corea». Años más tarde, tendrán que ser estas familias las que construyan aseos, añadan habitaciones aprovechando los patios o instalen los primeros colectores de aguas residuales. Para el agua corriente tendrán que esperar hasta 1971. La urbanización de las calles no será aprobada hasta 1980. En aquellos años, el barrio contaba ya con una de las asociaciones de vecinos más activas de la ciudad. Antes de la desintegración del movimiento asociativo, lograrán, en 1981, una de sus más importantes vindicaciones: la formalización de la propiedad de las viviendas, que pasará del Ayuntamiento a las familias ocupantes. (...)

Memorial Day for the sixteenth anniversary of the Alzamiento Nacional.1 (...) Up to 108 large, low-income families will benefit from the Casas del Aguinaldo. They have been built on the old unofficial settlement that the workers of the small, ceramic factories that proliferated in the area had built since the beginning of the century. The Casas del Aguinaldo2 have no running water nor sewers; nor do they have plumbing. Due to the clay in the soil and the lack of urbanisation, on rainy days the dusty streets turn into a quagmire. The overall size of each home, with three rooms and a courtyard is less than 100 m2. Some families have five or six children, so the population density is high. The neighbourhood does not have any kind of services nor connections to the town. On the whole the residents come from rural areas in the centre of the country. It won’t be long before the area is known as “Corea”. Years later it will be these families who have to build bathrooms, add rooms by using the courtyard or install the first waste water pipes. They would have to wait until 1971 to get running water. The paving of the streets will not be approved until 1980. In those days the neighbourhood already had one of the most active residents’ associations in the town. Before the association movement disintegrated,

they were to achieve one of their most important claims in 1981: official

recognition of home ownership that was to pass from the Council to the resident

families.

(...)

1. National Uprising.

2. Christmas Bonus Homes.

1. National Uprising.

2. Christmas Bonus Homes.

Gimnasio mixto del Club Deportivo Boxeo Fuerte y Constante, abierto y gestionado por Vicente Barrul, vecino del barrio y boxeador, en el centro cívico del sector Ventas Oeste. Barrio de La Inmaculada, «Corea». León.

Mixed gymnasium in the Fuerte y Constante (Strong and Tenacious) Boxing Club, opened and run by Vicente Barrul, resident of the neighbourhood and boxer, in the Civic Centre of the Ventas-Oeste sector. La Inmaculada neighbourhood, “Corea”, León.

Bloques de viviendas vistos desde la estación de tren. El tendido divide en dos partes la ciudad, separando los barrios obreros del casco histórico y de las zonas nobles. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Barrio de San Juanillo. Palencia.

Residential blocks seen from the train station. The railway line divide the city in two, separating the working-class neighbourhoods from the old town and the more elegant areas. In the vicinity of “Corea”. San Juanillo neighbourhood, Palencia.

Cementerio de los caídos del bando sublevado durante la Guerra Civil, junto a la ermita del Cerro de las Mártires. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Huesca.

Cemetery for the fallen of the rebel faction during the Civil War, next to the hermitage of Cerro de las Mártires. Vicinity of "Corea". Huesca.

Huesca, 22 de junio de 1953

Huesca, 22 de junio de 1953

( Huesca. June 22, 1953 )

(...) Tras recibir el homenaje de una compañía de infantería acuartelada en la ciudad, Franco acudirá a la recepción oficial en el salón del trono de la Diputación Provincial. Allí esperan el presidente de la misma, Fidel Lapetra, y el alcalde de la ciudad, el falangista José Gil Cávez, quienes le impondrán la medalla de oro de la provincia, el escudo de la ciudad y el título de hijo adoptivo de Huesca. En la catedral, la siguiente parada, aguarda el prelado de la diócesis, Lino Rodrigo Ruesca, quien le impondrá la medalla de Hermano Mayor Honorario de la Cofradía del Santo Cristo de los Milagros y San Lorenzo. Más tarde, el jefe del Estado acudirá al acto de bendición del nuevo edificio del Gobierno Civil. También tendrá tiempo para inaugurar, finalmente, un sanatorio para tuberculosos en las afueras de la ciudad: el Hospital Provincial Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, cuyas obras comenzaron en 1944. Este cuenta con ciento noventa camas para enfermos. Rodeado por los asentamientos chabolistas al pie del Cerro de las Mártires, junto a él será construido el Grupo Pamplona y Blasco (que toma su nombre del Gobernador Civil), las «casetas bajas», origen del barrio del Perpetuo Socorro, en el que serán reubicadas las familias desplazadas del centro por las expropiaciones para la construcción del nuevo palacio episcopal en la plaza de la Catedral. (...)

(...) After being paid homage by an infantry company stationed in the town, Franco will attend an official reception in the throne room at the Provincial Government. Waiting for him there will be the President of the local government, Fidel Lapetra, and the town’s mayor, the Falangist José Gil Cávez, who will award him the Provincial gold medal, the town emblem and the title of adopted son of Huesca. Waiting for him at the next stop, the cathedral, is the diocesan prelate, Lino Rodrigo Ruesca, who will award him with the medal of Hermano Mayor Honorario de la Cofradía del Santo Cristo de los Milagros y San Lorenzo 1. Later the head of State will attend the blessing of the new Civil Government building. He will also have time to finally inaugurate a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients on the town’s outskirts: the Hospital Provincial Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, the construction of which began in 1944. It has one hundred and ninety beds for the sick. Surrounded by the shanty towns at the foot of the hill known as Cerro de las Mártires, the block known as the Grupo Pamplona y Blasco 2 will be built next to it, so-called “low huts” coming from the neighbourhood of Perpetuo Socorro, to rehouse families displaced from the centre by the expropriation of their homes so as to build the new episcopal palace in the Cathedral square. (...)

1. Honorary Elder Brother of the Brotherhood of the Holy Christ of Miracles and Saint Lorenzo. 2. Named after the Civil Governor.

1. Honorary Elder Brother of the Brotherhood of the Holy Christ of Miracles and Saint Lorenzo. 2. Named after the Civil Governor.

Vista del barrio del Perpetuo Socorro (izquierda) y del hospital para tuberculosos Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, inaugurado por Francisco Franco en 1953 (derecha), desde el monumento de 2014 a las víctimas de la represión franquista en el Cerro de las Mártires. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Huesca.

“CNT. En recuerdo de todos los antifascistas, hombres y mujeres que sufrieron la represión, la guerra, la cárcel, el exilio y la muerte, para que su vida, lucha y ejemplo no caigan en el olvido.”

“CNT. En recuerdo de todos los antifascistas, hombres y mujeres que sufrieron la represión, la guerra, la cárcel, el exilio y la muerte, para que su vida, lucha y ejemplo no caigan en el olvido.”

View of the Perpetuo Socorro neighbourhood (left) and the Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Hospital for tuberculosis patients, inaugurated by Francisco Franco in 1953 (right), from the monument to the victims of repression during the Franco regime at Cerro de las Mártires. Vicinity of "Corea". Huesca.

"CNT (National Confederation of Labor, Anarchist Union). In memory of all antifascist men and women who suffered repression, war, prison, exile and death, so that their life, struggle and example do not fall into oblivion”.

"CNT (National Confederation of Labor, Anarchist Union). In memory of all antifascist men and women who suffered repression, war, prison, exile and death, so that their life, struggle and example do not fall into oblivion”.

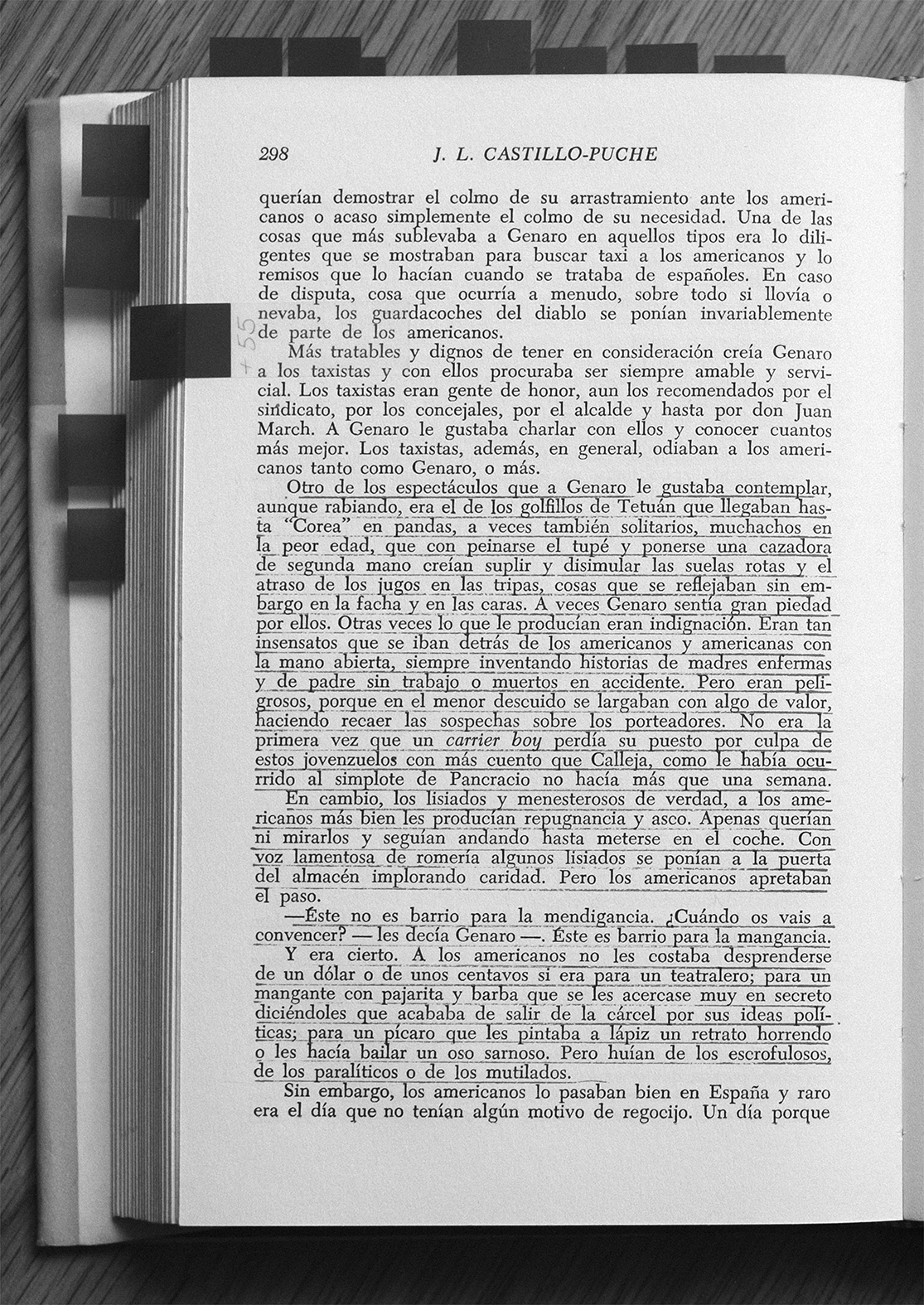

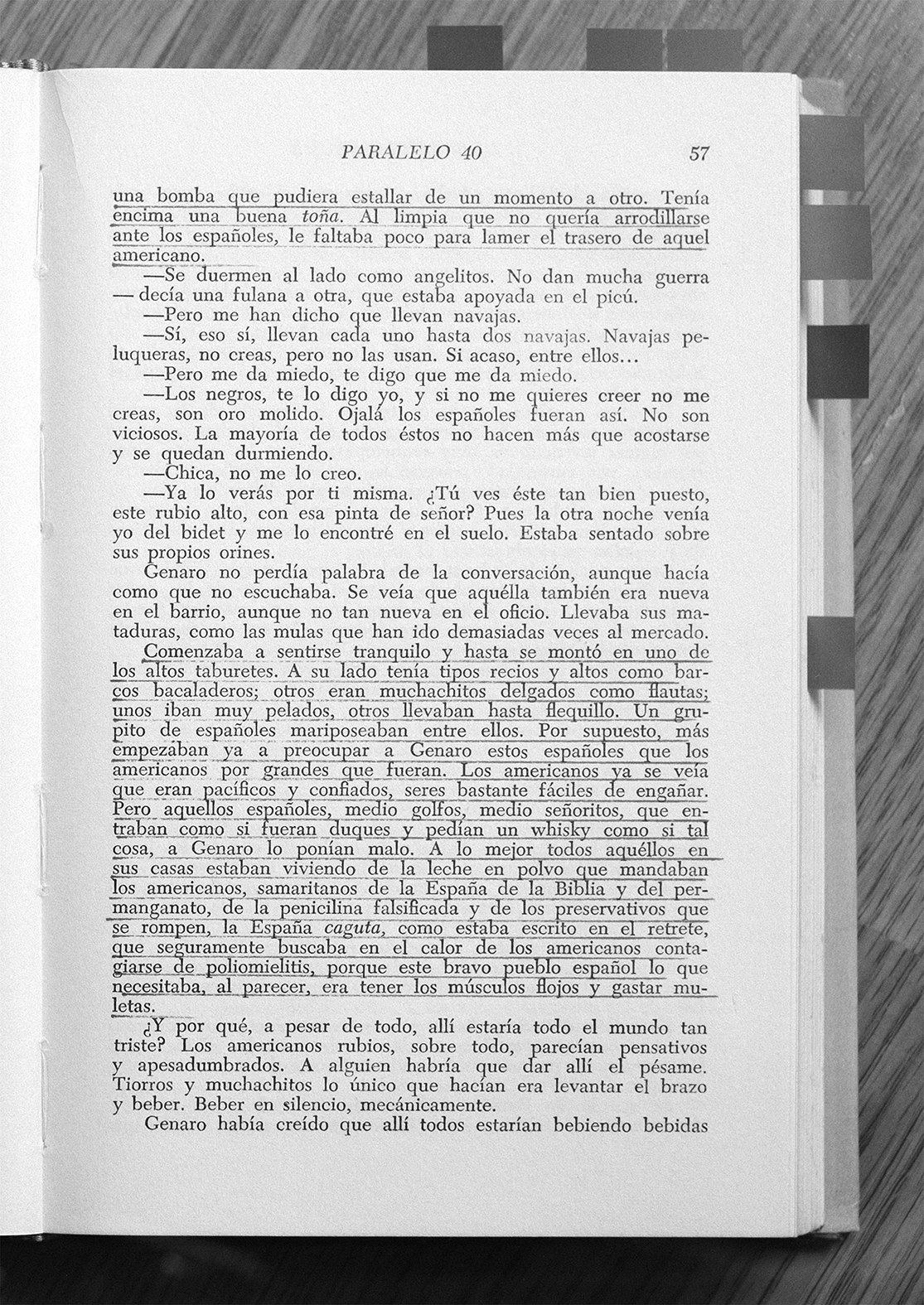

Paralelo 40

Paralelo 40

Abril de 1963. Ocho años después de que el autor, recién casado, tomase un piso en «Corea», el primero de los grandes bloques que los estadounidenses

habitaron en Madrid, la editorial Destino logrará publicar la primera

y única edición de Paralelo 40, de José Luis Castillo-Puche. Pocos días

después de la aparición de la novela, el historiador, académico de las letras y

político fascista Melchor Fernández Almagro, escribirá: «Es una novela

documental en el grado necesario para convertirse, llegado el momento, en

crónica histórica. De un contacto muy directo con la realidad certísima de la

irrupción norteamericana en Madrid». Para entonces, el escritor

había logrado alcanzar cierto prestigio en el mundo de las letras: Premio

Nacional de Periodismo (1952) y de Novela (1954). En 1956, publicará en Buenos

Aires Sin camino (1949), su primera novela, cuyo manuscrito logró salvar

de la quema en España, aunque no de la prohibición, al menos hasta 1963, cuando,

finalmente, en el contexto de la tímida apertura ejercida por Manuel Fraga como

ministro de Información y Turismo, se permitió su distribución. Sin embargo, ni

el prestigio ganado, ni las aún estrictas condiciones de censura facilitarán la

impresión de Paralelo 40, que será duramente atacada y recortada por la

censura. «Demasiado realista», así

será descrita la novela en los informes de los censores.

April 1963. Eight years after the

author, newly married, took a flat in “Corea”, the first of the large blocks

that the North Americans inhabited in Madrid, the publisher Destino will manage

to publish the first and only edition of Paralelo

40, by José Luis Castillo-Puche. A few days after the novel appeared the

historian, arts academic and fascist politician Melchor Fernández Almagro, will

write: “This is a documentary novel of the standard required to become, when

the time comes, a chronicle of history. It has a very true sense of the reality

of the North Americans bursting into Madrid”. At that time the writer had

managed to achieve a certain amount of prestige in the literary world: National

Prize for Journalism (1952) and for a Novel (1954). In 1956 he will publish his

first novel Sin camino (‘Without a

way’) in Buenos Aires (1949), having managed to rescue the manuscript from

being burnt in Spain, though not from being prohibited, at least not until 1963

when finally with the gentle opening-up practised by Manuel Fraga as Minister

of Information and Tourism, its distribution was allowed. However neither the

prestige it earned, nor the continuing strict conditions of censorship made it

easy for Paralelo 40 to be printed, and

it will be harshly criticised and cut by the censors. “Too realistic” was how

the censors’ reports described the novel.

One more block. It was going to look good, maybe less ambitious than others, but more comfortable. Little by little architects and master builders had agreed.

It was also mainly a house for Americans. They were the only ones who could afford them. They even had air conditioning, like their cars. At first the Americans had lived where they could, in pretty slipshod houses, in which there was hardly an alcove in the office to embed the refrigerators, the tall ones, the almost round ones, the great and sumptuous refrigerators that were the most important piece of furniture for them. The refrigerator for the Americans, more than a domestic object, was a kind of sacred idol. Cooking stoves were eliminated as the Americans did not want them. Now all these houses had electricity or butane gas. The stoves were mere mice catchers anymore. And the floors were now genuine hardwood and not the previous dingy affairs. Construction had arisen in the glow of the mighty dollar —Americans had to be pleased. Realtors, contractors, architects, engineers, had smelled business at once: luxury housing for the Americans, with embedded closets and even a garden terrace.

Castillo-Puche, José Luis (1963)

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo

40. Primer informe. 14 de abril de 1962.

«Trata de recoger el impacto de la presencia de tropas americanas en Madrid, describiendo sus fueros y sus desafueros. Particularmente, el contraste de la vida que ellos imponen con la miseria que se respira al lado de su zona residencial. El protagonista, sin embargo, es un español, obrero, resentido, imbuido de ideas revolucionarias, que de continuo está alzando su protesta y sus proyectos de revancha. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Primer Informe-Anexo. 7 de mayo de 1962.

«(...) Un comunista salido de la cárcel, un albañil torvo y resentido, a cuyo padre fusilaron los nacionales. La trama de toda la acción descrita, destacada y novelada la constituye la presencia de los americanos en España, en virtud de “eso tan pomposo como enigmático que se llama tratado hispanoamericano”. Presencia “masiva” de norteamericanos en una España encanallada y sin coraje, con cuarteles generales propios y con bases aéreas y navales exclusivamente suyas, puesto que ni siquiera se alude nunca a la utilización conjunta. Ocupación de una España que ha vendido, sin pena ni gloria y sin ningún provecho y beneficio económico, su soberanía, y en la que privan por sus respetos los soldados rubios y negros a quienes sirven dócil y servilmente muchos indefensos españoles, acuciados por la extrema pobreza de sus hogares, o por su condición de chulos y de rameras y de ninfómanas, o por la carencia de mejores horizontes patrios. (...)

»En definitiva, visión de un Madrid y de una España a través del prisma que ofrece la mentalidad demoledora de un rojo español reconcomido por el resentimiento y la derrota de los suyos; de un ácrata inculto, de un albañil sin instrucción ni formación alguna; de un comunista que sirve al Partido azuzando a los españoles contra los norteamericanos, con el pretexto del patriotismo y del sentimiento de independencia nacional, para crear conflictos y dificultades al Régimen actual y así poder ir acercándose a los objetivos que el comunismo internacional persigue en España. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Segundo Informe. 15 de junio de 1962.

«(…) Un juego tremendista de una burda pornografía en maridaje con un insobornable odio político de clase. Lo subconsciente anarco-político y lo freudiano sexual, morboso y vicioso del personaje central —Genaro— y de la mayoría de tipos o figuras plasmadas por el Autor, se percibe en la casi totalidad de la obra, y desde la primera página hasta su último capítulo se pretende dar un aspecto teratológico de nuestro actual momento español. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Segundo Informe-Anexo. Sin fecha.

«(...) Dentro de un marco donde se mezcla la más grosera y manoseada pornografía (...) con los ataques a las clases y estamentos sociales españoles —Iglesia, Clero, Ejército, Sindicatos, clases rectoras, etc.— para llevar el ánimo del lector a la conclusión de que en la España actual no existe una conciencia limpia y sana, y de que todo es trampa, bazofia, mentira y prevaricación. (...)»

«Trata de recoger el impacto de la presencia de tropas americanas en Madrid, describiendo sus fueros y sus desafueros. Particularmente, el contraste de la vida que ellos imponen con la miseria que se respira al lado de su zona residencial. El protagonista, sin embargo, es un español, obrero, resentido, imbuido de ideas revolucionarias, que de continuo está alzando su protesta y sus proyectos de revancha. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Primer Informe-Anexo. 7 de mayo de 1962.

«(...) Un comunista salido de la cárcel, un albañil torvo y resentido, a cuyo padre fusilaron los nacionales. La trama de toda la acción descrita, destacada y novelada la constituye la presencia de los americanos en España, en virtud de “eso tan pomposo como enigmático que se llama tratado hispanoamericano”. Presencia “masiva” de norteamericanos en una España encanallada y sin coraje, con cuarteles generales propios y con bases aéreas y navales exclusivamente suyas, puesto que ni siquiera se alude nunca a la utilización conjunta. Ocupación de una España que ha vendido, sin pena ni gloria y sin ningún provecho y beneficio económico, su soberanía, y en la que privan por sus respetos los soldados rubios y negros a quienes sirven dócil y servilmente muchos indefensos españoles, acuciados por la extrema pobreza de sus hogares, o por su condición de chulos y de rameras y de ninfómanas, o por la carencia de mejores horizontes patrios. (...)

»En definitiva, visión de un Madrid y de una España a través del prisma que ofrece la mentalidad demoledora de un rojo español reconcomido por el resentimiento y la derrota de los suyos; de un ácrata inculto, de un albañil sin instrucción ni formación alguna; de un comunista que sirve al Partido azuzando a los españoles contra los norteamericanos, con el pretexto del patriotismo y del sentimiento de independencia nacional, para crear conflictos y dificultades al Régimen actual y así poder ir acercándose a los objetivos que el comunismo internacional persigue en España. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Segundo Informe. 15 de junio de 1962.

«(…) Un juego tremendista de una burda pornografía en maridaje con un insobornable odio político de clase. Lo subconsciente anarco-político y lo freudiano sexual, morboso y vicioso del personaje central —Genaro— y de la mayoría de tipos o figuras plasmadas por el Autor, se percibe en la casi totalidad de la obra, y desde la primera página hasta su último capítulo se pretende dar un aspecto teratológico de nuestro actual momento español. (...)»

Expediente de Censura 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Segundo Informe-Anexo. Sin fecha.

«(...) Dentro de un marco donde se mezcla la más grosera y manoseada pornografía (...) con los ataques a las clases y estamentos sociales españoles —Iglesia, Clero, Ejército, Sindicatos, clases rectoras, etc.— para llevar el ánimo del lector a la conclusión de que en la España actual no existe una conciencia limpia y sana, y de que todo es trampa, bazofia, mentira y prevaricación. (...)»

Censorship File

1850-62. Paralelo 40. First report.

April 14, 1962

It tries to capture the impact of the American troops’ presence in Madrid, describing their privileges and their immunity. In particular, the contrast between the life they lead in contrast with the misery that is palpable right next to where they live. The main character, however, is a Spaniard, a labourer, resentful, imbued with revolutionary ideas and who is continuously protesting and seeking revenge. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Appendix to first report. May 7, 1962

“(...) A communist out of prison, a grim, resentful builder whose father was shot dead by the Nationals. The plot of all the action described, highlighted and made into a novel is about the American presence in Spain, along the lines of ‘this so-called Spanish-American treaty is as pompous as it is enigmatic’. An ‘enormous’ presence of North Americans in a Spain that has prostituted itself and is weak, with its own barracks and air and naval bases that are exclusively theirs, considering there is never even any mention of joint usage. Occupation of a Spain that has sold, without pain or glory and with no financial advantage or benefit, its own sovereignty, and where they are deprived of respect by the blond and black soldiers whom many defenceless Spanish serve meekly, driven by the extreme poverty in their homes, or because they are pimps and whores and nymphomaniacs, or for the lack of better patriotic horizons. (...)

In a word, a vision of a Madrid and Spain through the prism offered by the destructive mentality of a Spanish rojo (Red) bearing a grudge out of resentment and the defeat of his side; from an uncouth anarchist, a builder without any kind of education or training; from a Communist who serves the Party inciting the Spanish against the North Americans under the pretext of patriotism and a sentiment of national independence, so as to create conflicts and difficulties with the current Regime and that way be able to get closer to the objectives that international communism is pursuing in Spain. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Second report. June 15, 1962

“(…) An alarmist trick of crude pornography merged with an incorruptible political hate of class. The anarchic-political subconscious and the Freudian sexual, morbid and vicious nature of the central character —Genaro— and of most of the types and people created by the Author, are seen in nearly the whole work, and from the first page to the last he is trying to dub our current time in Spain as something abnormal. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Second Report-Appendix. No date.

“(…) Within a framework mixing the most vulgar and grubby pornography (…) with attacks on the Spanish social classes and establishments —Church, Clergy, Army, Unions, ruling classes, etc.— to lead the reader to the conclusion that in Spain today no clean, healthy conscience can be found, and that everything is a trap, pigswill, lies and perversion of justice. (...)”

It tries to capture the impact of the American troops’ presence in Madrid, describing their privileges and their immunity. In particular, the contrast between the life they lead in contrast with the misery that is palpable right next to where they live. The main character, however, is a Spaniard, a labourer, resentful, imbued with revolutionary ideas and who is continuously protesting and seeking revenge. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Appendix to first report. May 7, 1962

“(...) A communist out of prison, a grim, resentful builder whose father was shot dead by the Nationals. The plot of all the action described, highlighted and made into a novel is about the American presence in Spain, along the lines of ‘this so-called Spanish-American treaty is as pompous as it is enigmatic’. An ‘enormous’ presence of North Americans in a Spain that has prostituted itself and is weak, with its own barracks and air and naval bases that are exclusively theirs, considering there is never even any mention of joint usage. Occupation of a Spain that has sold, without pain or glory and with no financial advantage or benefit, its own sovereignty, and where they are deprived of respect by the blond and black soldiers whom many defenceless Spanish serve meekly, driven by the extreme poverty in their homes, or because they are pimps and whores and nymphomaniacs, or for the lack of better patriotic horizons. (...)

In a word, a vision of a Madrid and Spain through the prism offered by the destructive mentality of a Spanish rojo (Red) bearing a grudge out of resentment and the defeat of his side; from an uncouth anarchist, a builder without any kind of education or training; from a Communist who serves the Party inciting the Spanish against the North Americans under the pretext of patriotism and a sentiment of national independence, so as to create conflicts and difficulties with the current Regime and that way be able to get closer to the objectives that international communism is pursuing in Spain. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Second report. June 15, 1962

“(…) An alarmist trick of crude pornography merged with an incorruptible political hate of class. The anarchic-political subconscious and the Freudian sexual, morbid and vicious nature of the central character —Genaro— and of most of the types and people created by the Author, are seen in nearly the whole work, and from the first page to the last he is trying to dub our current time in Spain as something abnormal. (...)”

Censorship File 1850-62. Paralelo 40. Second Report-Appendix. No date.

“(…) Within a framework mixing the most vulgar and grubby pornography (…) with attacks on the Spanish social classes and establishments —Church, Clergy, Army, Unions, ruling classes, etc.— to lead the reader to the conclusion that in Spain today no clean, healthy conscience can be found, and that everything is a trap, pigswill, lies and perversion of justice. (...)”

El general Franco saluda mientras el avión del presidente de Estados Unidos aterriza en la base aérea de Torrejón. A la derecha, John Davis Lodge, embajador de Estados Unidos. 21 de diciembre de 1959.

NOTA: Las imágenes aquí mostradas provienen del Departamento de Información y Cultura de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en España. El archivo documental cuenta con una colección de 7.000 imágenes de dominio público custodiadas por la Biblioteca del Convento de Trinitarios Descalzos en Alcalá de Henares. Las imágenes fueron desclasificadas en 1991 y entregadas a la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares que, tras digitalizarlas, las puso a disposición del público en 2008. La autoría de las fotografías no figura en el registro de la biblioteca. Todas las imágenes están sujetas a una licencia Creative Commons.

NOTA: Las imágenes aquí mostradas provienen del Departamento de Información y Cultura de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en España. El archivo documental cuenta con una colección de 7.000 imágenes de dominio público custodiadas por la Biblioteca del Convento de Trinitarios Descalzos en Alcalá de Henares. Las imágenes fueron desclasificadas en 1991 y entregadas a la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares que, tras digitalizarlas, las puso a disposición del público en 2008. La autoría de las fotografías no figura en el registro de la biblioteca. Todas las imágenes están sujetas a una licencia Creative Commons.

General Franco salutes as the United States President's (Dwight D. Eisenhower) plane lands at the Torrejón airbase. On the right, John Davis Lodge, U.S. Ambassador. December 21, 1959.

NOTE: The pictures shown here come from the Cultural and Information Department of the United States Embassy in Spain. The document archive has a collection of seven thousand images of public domain kept by the Biblioteca del Convento de Trinitarios Descalzos (the Convent’s library) in Alcalá de Henares. The images were declassified in 1991 and given to the University of Alcalá de Henares. This institution put them into digital format and made them available to the public in 2008. The name of the photographer does not appear in the register. All the images are under a Creative Commons licence.

NOTE: The pictures shown here come from the Cultural and Information Department of the United States Embassy in Spain. The document archive has a collection of seven thousand images of public domain kept by the Biblioteca del Convento de Trinitarios Descalzos (the Convent’s library) in Alcalá de Henares. The images were declassified in 1991 and given to the University of Alcalá de Henares. This institution put them into digital format and made them available to the public in 2008. The name of the photographer does not appear in the register. All the images are under a Creative Commons licence.

Un retrato del Presidente Eisenhower en la abarrotada Gran Vía de Madrid durante el desfile de bienvenida dado en su honor por el régimen franquista. 21 de diciembre de 1959.

A portrait of Eisenhower on the crowded streets of Madrid during the Regime's parade celebrating the President's visit. December 21, 1959.

Madrid, 26 de septiembre de 1953

( Madrid. September 22, 1953 )

Palacio de Santa Cruz. James Clement Dunn, embajador de Estados Unidos; Alberto Martín-Artajo, ministro de Asuntos Exteriores, y Manuel Arburúa, ministro de Comercio, estampan su firma en una serie de documentos que zanjarán, tan solo dos meses después de la firma del armisticio en Corea y en plena emergencia de la guerra fría, la controvertida «cuestión española». Pero los documentos no cuentan la historia, sirven a su escritura. Así, los Pactos de Madrid culminarán la labor propagandística cuya misión ha sido desplazar la mirada de las derechas occidentales hacia una nueva y más alineada percepción. En adelante, y superpuesto a las antiguas afinidades, un viejo rostro, el del anticomunismo, pero más en sintonía con los tiempos, mirará hacia el enemigo común, la amenaza soviética. Un nuevo perfil diplomático, el liberal-cristiano, deberá reemplazar al anquilosado falangismo. Cómplice, pero menos connotado, su misión será distraer de la «particularidad española» o, al menos, hacerla presentable. La dictadura conseguirá lo que, desde la derrota del Eje en 1945, había perseguido: su supervivencia a largo plazo, garantizada en su legitimación internacional. Es sabido que la urgencia impone, y a la luz de este estado de las cosas la excepción será la regla. La puerta al Mediterráneo, afianzada y bendecida. La democracia, suspendida para defender la democracia. (...)

Palacio

de Santa Cruz.

James Clement Dunn, United States ambassador; Alberto Martín-Artajo, Minister

of Foreign Affairs, and Manuel Arburúa, Minister of Trade, sign a series of

documents that will resolve, only two months since the armistice was signed in

Korea and at the height of the Cold War, the controversial “Spanish question”.

But the documents do not tell the story, they act as deeds. This was how the

Pact of Madrid was to bring the propaganda work to an end, whose mission had

been to turn the gaze of the western right-wing towards a new, more aligned

perception. From here on, and superimposed on former sympathies, an old face,

the anti-Communist one but more in tune with the times, will look towards the

common enemy, the Soviet threat. A new diplomatic profile, the

Liberal-Christian, should replace the out-dated Falangist one. An accomplice,

but less noticeable, its mission will distract from the “Spanish particularity”

or at least make it more presentable. The dictatorship will achieve what, since

the defeat of the Axis in 1945, it had pursued: its long-term survival,

guaranteed with international legitimation. It is understood this is urgent and

in view of this state of affairs the exception will be the rule. The door to

the Mediterranean secured and blessed. Democracy suspended to defend democracy. (...)

El viejo monasterio de Santa María de la Rábida, en la ciudad española de Huelva, recibió a un visitante procedente de América el 4 de agosto de 1955, justo 463 años después de otra mañana de agosto en que vio cómo otro visitante partía para descubrir dicho continente. Colón zarpó del puerto de esta ciudad, conocido como Palos, en su primer viaje. El americano mencionado era John Davis Lodge, el embajador de Estados Unidos, que obsequió al monasterio con una bandera estadounidense y una caja con tierra de Mount Vernon, donde nació el primer presidente de Estados Unidos. En este grupo, de izquierda a derecha, aparecen el secretario de la Real Sociedad Colombina; fra Arturo; el embajador Lodge; Frank Howell, director de Trans World Airlines, y el alcalde de Huelva.

The old monastery of Santa María de la Rábida, in Huelva, Spain, received a visit from America on August 4, 1955, exactly 463 years after on another August morning it saw a different visitor leave to discover America. Colombus set sail from this town’s port, known as Palos, on his very first voyage. Today’s American is John Davis Lodge, U.S. Ambassador, who gave the monastery an American flag and a box containing earth from Mount Vernon where the first President of the United States was born. In this group, from left to right, are the Secretary of the Real Sociedad Colombina, Father Arturo, Ambassador Lodge, Frank Howell, Director of Trans-World Airlines and the mayor of Huelva.

Poco antes de ser condecorados en reconocimiento a la labor prestada, oficiales estadounidenses y españoles posan junto a la bomba atómica recuperada en las cercanías de Palomares en 1966.

Spanish and American officers before the official ceremony to award military medals in recognition of involvement in the rescue work of the Palomares atomic bomb in 1966.

Another of the shows that Genaro liked to witness, raging internally, was that of the Tetuán urchins who came to “Corea”, alone or in gangs, boys of the worst age, that thought combing a toupee and putting on a second hand jacket disguised their broken soles and empty stomachs, evidenced nevertheless by their shabbiness and the look on their faces. Sometimes Genaro felt great pity for them. Other times he was indignant. They foolishly followed the Americans around, hands outstretched, making up sick mothers and parents killed in an accident or unemployed. But they were dangerous, taking advantage of the slightest carelessness to take off with valuables, and have the guilt fall on the porters. It was not the first time that a carrier boy lost his position because of these youngsters with the gift of the gab, as it had happened to the simpleton Pancracio not more than a week ago.

On the other hand, the Americans found the cripples and the truly needy rather disgusting. They averted their eyes on the way to their car. In the plaintive tone of a pilgrim, some cripples loitered at around the warehouse imploring charity. But the Americans hastened.

—Once and for all, this is not a neighbourhood for begging! —Genaro told them—. This is a neighborhood for swindling.

And it was true. It was not hard for the Americans to let go of a dollar or a few cents if it was for a charlatan; for a fraudster with bow tie and beard who approached them in confidence calming to have just come out of prison for his political ideas; for a rascal who drew horrendous portraits or made a mangy bear dance for them. But they fled from the scrofulous, from the paralysed or the mutilated.

Castillo-Puche, José Luis (1963)

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

El 28 de septiembre de 1964, Faustino García-Moncó, director general del Banco de Bilbao y fututo ministro de Comercio, firmó un acuerdo de préstamo con el Export-Import Bank de Washington por valor de 2.500.000 dólares. El importe se utilizaría para ayudar a empresas españolas a adquirir equipos y maquinaria en Estados Unidos y contribuir a la expansión industrial y el desarrollo económico de España.

On September 28, 1964, Faustino García-Moncó, Director General of the Banco de Bilbao, signed a loan agreement with the Washington Export-Import Bank, for the sum of 2,500,000 dollars. The money would be used to help Spanish firms buy equipment and machinery from the United States and to help industrial growth and economic development in Spain.

Un escuadrón de patrulla marítima rinde homenaje a Colón. El comandante de la Marina estadounidense William T. Rapp, de Irvington (Nueva Jersey), jefe del Escuadrón de Patrulla 10, posa con la corona que su avión P2V Neptune dejó caer al canal desde donde los tres barcos de Cristobal Colón zarparon en 1492 para descubrir el Nuevo Mundo. La inscripción dice: «En honor de Cristobal Colón y los valientes marineros españoles que tal día como hoy del año 1492 cambiaron el curso de la historia». 13 de octubre de 1959.

A Navy Patrol Squadron pays homage to Columbus. Commander William T. Rapp, USN, of Irvington, New Jersey, commanding officer of Navy Patrol Squadron Ten poses with the wreath that his P2V Neptune patrol bomber dropped in the straits from where Christopher Columbus’ three vessels set sail in 1492 to discover the New World. October 13, 1959.

A Navy Patrol Squadron pays homage to Columbus. Commander William T. Rapp, USN, of Irvington, New Jersey, commanding officer of Navy Patrol Squadron Ten poses with the wreath that his P2V Neptune patrol bomber dropped in the straits from where Christopher Columbus’ three vessels set sail in 1492 to discover the New World. October 13, 1959.

El jefe de la base hispano-estadounidense pasa revista mientras lleva cogido de la mano a un niño de Zaragoza, enfermo de leucemia, al que habían nombrado jefe de la base por un día. Los miembros de las fuerzas aéreas regalaron al niño un uniforme de oficial estadounidense y le dieron medicinas para su tratamiento. Poco después el niño, Andrés Cuello, falleció.

The head of the American-Spanish base reviews the troops while holding the hand of a child from Zaragoza suffering from leukaemia, who has been nominated head of the base for a day. Members of the Air Force gave the child an American officer's uniform as well as medicine for his treatment. Shortly after the boy, Andrés Cuello, died.

He began to feel calm and even climbed one of the tall stools. At his side he had tough, tall men like cod boats; others were thin, flute-like boys; some

sporting crew cuts, others wore bangs. A small group of Spaniards lingered. Of course, these Spaniards worried Genaro more than the Americans, no matter their size. The Americans were peaceful and trusting, easy enough to deceive. But those Spaniards, half-blackguards, half-gentlemen, who entered as if they were dukes and asked for a whiskey like anything, made Genaro sick to his stomach. More often than not they were living on the powdered milk that the Americans sent, Samaritans of the Bible-and-permanganate Spain, of the fake penicillin and of the condoms-that-brake Spain, the “caguta” Spain, as read in the toilet. They might have sought to get polio from the Americans in that closeness. Because that’s what the brave Spanish people apparently needed crutches and loose muscles.

sporting crew cuts, others wore bangs. A small group of Spaniards lingered. Of course, these Spaniards worried Genaro more than the Americans, no matter their size. The Americans were peaceful and trusting, easy enough to deceive. But those Spaniards, half-blackguards, half-gentlemen, who entered as if they were dukes and asked for a whiskey like anything, made Genaro sick to his stomach. More often than not they were living on the powdered milk that the Americans sent, Samaritans of the Bible-and-permanganate Spain, of the fake penicillin and of the condoms-that-brake Spain, the “caguta” Spain, as read in the toilet. They might have sought to get polio from the Americans in that closeness. Because that’s what the brave Spanish people apparently needed crutches and loose muscles.

Castillo-Puche, José Luis (1963)

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

Paralelo 40. Barcelona: Destino.

Mausoleo de la familia March en el cementerio municipal. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Palma de Mallorca. Joan March, banquero y contrabandista perseguido y encarcelado por sus actividades económicas irregulares, fue uno de los principales y más activos financiadores del golpe de estado de 1936. Durante la dictadura, y bajo su protección, cerraría grandes operaciones financieras y sería conocido popularmente como «el banquero de Franco».

Mausoleum of the March family in the municipal cemetery. Vicinity of "Corea". Palma de Mallorca. Juan March, banker and smuggler persecuted and imprisoned in 1932 for his irregular economic activities, was one of the main and more active financiers of the coup d'etat of 1936. During the dictatorship, and under its wing, he closed massive financial deals and was commonly known as "Franco's banker".

Pequeño altar a Ceferino Giménez Malla, «el Pelé», que fue condenado a muerte por interceder en el linchamiento de un sacerdote en 1936. Renunció a desprenderse del rosario que llevaba cuando fue detenido, lo que impidió su indulto. Fue fusilado en Barbastro y murió gritando «¡Viva Cristo Rey!». En 1997 fue el primer gitano beatificado por la Iglesia católica. Parroquia de la Inmaculada. Barrio de La Inmaculada, «Corea». León.

A small altar dedicated to Ceferino "el Pelé" Giménez Malla, who was condemned to death for interceding in the lynching of a priest in 1936. He refused to let go of the rosary he was holding when arrested, and this prevented his pardon. He was shot in Barbastro and died shouting “Long live Christ the King” (¡Viva Cristo Rey!). In 1997 he became the first gypsy to be beatified by the Catholic Church. La Inmaculada Parish, “Corea”. León.

Dos viviendas unifamiliares en el grupo de viviendas de Francisco Franco, «Corea». Barrio de San Juanillo. Palencia.

Two semi-detached single-family homes on the Francisco Franco estate, "Corea". San Juanillo neighbourhood. Palencia.

«Casa. Aquí mandamos nosotros.» Restos de juegos infantiles sobre los raíles del proyecto parado de adaptación del antiguo tendido del Feve (Ferrocarril Español de Vía Estrecha) para la circulación de tranvías. Barrio de Las Ventas. León.

“Home. We’re in charge here.” Remains of a playground on the rails of a project never complete to adapt the old FEVE (Spanish Narrow Gauge Railway) coal line into a tram network. Las Ventas neighbourhood, León.

Antigua fábrica de Mildred-Pauni, cerrada en 2007 por suspensión de pagos. Inmediaciones del barrio del Perpetuo Socorro, «Corea». Polígono industrial Monzú. Huesca.

The old Mildred-Pauni factory, closed in 2007 after going into receivership. In the vicinity of the Perpetuo Socorro neighbourhood, “Corea”. Monzú industrial estate, Huesca.

Huesca, 26 de julio de 2007

Huesca, 26 de julio de 2007

( Huesca. July 26, 2007 )

(...) A las 8 de esta tarde han acudido alrededor de quinientas personas a la plaza de Navarra. La manifestación seguirá el mismo recorrido que la del pasado 1º de mayo, en la que ya fueron protagonistas las trabajadoras de Mildred. La pancarta de cabecera dice: «Huesca por Mildred. Ayuntamiento y Gobierno de Aragón: exigimos reindustrialización». La manifestación está convocada por el comité de empresa de Mildred-Pauni. Asisten las 398 trabajadoras afectadas por el cierre de la fábrica, en su mayoría migrantes de baja cualificación. (...)

Mildred inició un procedimiento de suspensión de pagos en 1999, nueve años después de su apertura. Sin embargo, fue en marzo de 2007 cuando, tras la pérdida de su mayor cliente, Lidl, que adquiría el 90 % de su producción, inició su liquidación. Para entonces la empresa acumulaba una deuda de veinte millones de euros. Las ayudas públicas para el apoyo y fortalecimiento empresarial, que alcanzaron para esta empresa el millón de euros, no sirvieron para mejorar su posición. Entre las medidas adoptadas para paliar la situación de las trabajadoras, el Gobierno regional quiso destacar los cursos de formación profesional continua (auxiliar de oficina, iniciación a la informática, aplicaciones informáticas de contabilidad, Office, monitor de tiempo libre, carretillero, técnicas de almacenaje), y las sesiones informativas, entrevistas y tutorías personalizadas impartidas por el INAEM, los sindicatos UGT y CC.OO., y la Fundación San Ezequiel Moreno. «La prioridad será la recolocación de la plantilla al completo» (...)

Al cierre de la pastelera se suman el cese de actividad en 2010 de Talleres Luna S.A., la última gran metalúrgica de Huesca, dedicada a la fabricación de equipos industriales, con 200 despidos tras un año de encierro en la fábrica; la planta de Moulinex de Barbastro, cuya deslocalización en 2004 supuso la pérdida de 271 empleos; la suspensión de actividad en noviembre de 2008 de Oscainox, especializada en la fabricación de mobiliario de acero, con un saldo de 64 empleados; el expediente de regulación de empleo de Ercros (Monzón), que redujo la plantilla de 125 a 32 trabajadores; el cierre en 2008 de APSAR (Apósitos Sanitarios Aragoneses), que puso a sus 21 empleadas en la calle; o el expediente de suspensión de empleo de Transportes Alonso, que afectó con 60 días sin empleo y sueldo a 77 de los 93 trabajadores en plantilla en 2009. Este no es el primer ciclo de desindustrialización que sufre la región. Se estima que entre 1980 y 1994 se perdieron alrededor de tres mil puestos de trabajo. (...)

Mildred inició un procedimiento de suspensión de pagos en 1999, nueve años después de su apertura. Sin embargo, fue en marzo de 2007 cuando, tras la pérdida de su mayor cliente, Lidl, que adquiría el 90 % de su producción, inició su liquidación. Para entonces la empresa acumulaba una deuda de veinte millones de euros. Las ayudas públicas para el apoyo y fortalecimiento empresarial, que alcanzaron para esta empresa el millón de euros, no sirvieron para mejorar su posición. Entre las medidas adoptadas para paliar la situación de las trabajadoras, el Gobierno regional quiso destacar los cursos de formación profesional continua (auxiliar de oficina, iniciación a la informática, aplicaciones informáticas de contabilidad, Office, monitor de tiempo libre, carretillero, técnicas de almacenaje), y las sesiones informativas, entrevistas y tutorías personalizadas impartidas por el INAEM, los sindicatos UGT y CC.OO., y la Fundación San Ezequiel Moreno. «La prioridad será la recolocación de la plantilla al completo» (...)

Al cierre de la pastelera se suman el cese de actividad en 2010 de Talleres Luna S.A., la última gran metalúrgica de Huesca, dedicada a la fabricación de equipos industriales, con 200 despidos tras un año de encierro en la fábrica; la planta de Moulinex de Barbastro, cuya deslocalización en 2004 supuso la pérdida de 271 empleos; la suspensión de actividad en noviembre de 2008 de Oscainox, especializada en la fabricación de mobiliario de acero, con un saldo de 64 empleados; el expediente de regulación de empleo de Ercros (Monzón), que redujo la plantilla de 125 a 32 trabajadores; el cierre en 2008 de APSAR (Apósitos Sanitarios Aragoneses), que puso a sus 21 empleadas en la calle; o el expediente de suspensión de empleo de Transportes Alonso, que afectó con 60 días sin empleo y sueldo a 77 de los 93 trabajadores en plantilla en 2009. Este no es el primer ciclo de desindustrialización que sufre la región. Se estima que entre 1980 y 1994 se perdieron alrededor de tres mil puestos de trabajo. (...)

(...) At 8 o’clock this evening around five hundred

people congregated in Plaza de Navarra. The demonstration will follow the same

route as the one on May 1st this year, led by Mildred workers. The

banner at its head read “Huesca with Mildred. City Council and government of

Aragon: we demand reindustrialization”. The demonstration has been convened by

the Mildred-Pauni business committee. The 398 workers affected by the factory

closure are all there, most of them low-qualified immigrants. (...)

Mildred began the process of bankruptcy in 1999, nine years after opening. However it was not until March 2007, after losing its biggest client, Lidl, which took 90% of its production, that it began liquidation. At that time the company had amassed a twenty million euro debt. State aid for business support came to a million euros for this company so did not improve their situation. Among the measures taken to ease the 398 workers’ situation, the regional Government pointed to continuing professional training courses and information sessions, interviews and personalised tutorials given by the INAEM 1, the trade unions UGT and CC.OO., and the San Ezequiel Moreno Foundation. “Our priority is to relocate the entire staff”. (...)

In addition to the closure of the pastry making factory, Talleres Luna S.A., the last great metallurgy business in Huesca, manufacturing industrial equipment, closed down in 2010 sacking 200 people after a year squatting in the factory; the Moulinex plant in Barbastro relocated in 2004 causing the loss of 271 jobs; the closure in 2008 of Oscainox that specialised in manufacturing steel furniture, with a loss of 64 jobs; the layoffs at Ercros (Monzón) that cut the staff from 125 to 32; the closure of APSAR (Aragon Sanitary Bandages) in 2008 leaving 21 employees jobless; or the suspension from work and pay in Transportes Alonso that affected 77 of the 93 employees for 60 days in 2009. This is not the first cycle of deindustrialisation that the region has suffered. It is estimated that between 1980 and 1994 around 3,000 jobs were lost. (...)

1. Aragon Employment Office.

Mildred began the process of bankruptcy in 1999, nine years after opening. However it was not until March 2007, after losing its biggest client, Lidl, which took 90% of its production, that it began liquidation. At that time the company had amassed a twenty million euro debt. State aid for business support came to a million euros for this company so did not improve their situation. Among the measures taken to ease the 398 workers’ situation, the regional Government pointed to continuing professional training courses and information sessions, interviews and personalised tutorials given by the INAEM 1, the trade unions UGT and CC.OO., and the San Ezequiel Moreno Foundation. “Our priority is to relocate the entire staff”. (...)

In addition to the closure of the pastry making factory, Talleres Luna S.A., the last great metallurgy business in Huesca, manufacturing industrial equipment, closed down in 2010 sacking 200 people after a year squatting in the factory; the Moulinex plant in Barbastro relocated in 2004 causing the loss of 271 jobs; the closure in 2008 of Oscainox that specialised in manufacturing steel furniture, with a loss of 64 jobs; the layoffs at Ercros (Monzón) that cut the staff from 125 to 32; the closure of APSAR (Aragon Sanitary Bandages) in 2008 leaving 21 employees jobless; or the suspension from work and pay in Transportes Alonso that affected 77 of the 93 employees for 60 days in 2009. This is not the first cycle of deindustrialisation that the region has suffered. It is estimated that between 1980 and 1994 around 3,000 jobs were lost. (...)

1. Aragon Employment Office.

Las trabajadoras de la Standard Eléctrica aplauden mientras el dictador inaugura la fábrica. Archivo de la Asociación de Vecinos «El Tajo». Toledo, 1971.

Workers from the Standard Eléctrica clap during the inauguration of the factory by General Franco. Archive of the Neighbours Association "El Tajo". Toledo, 1971.

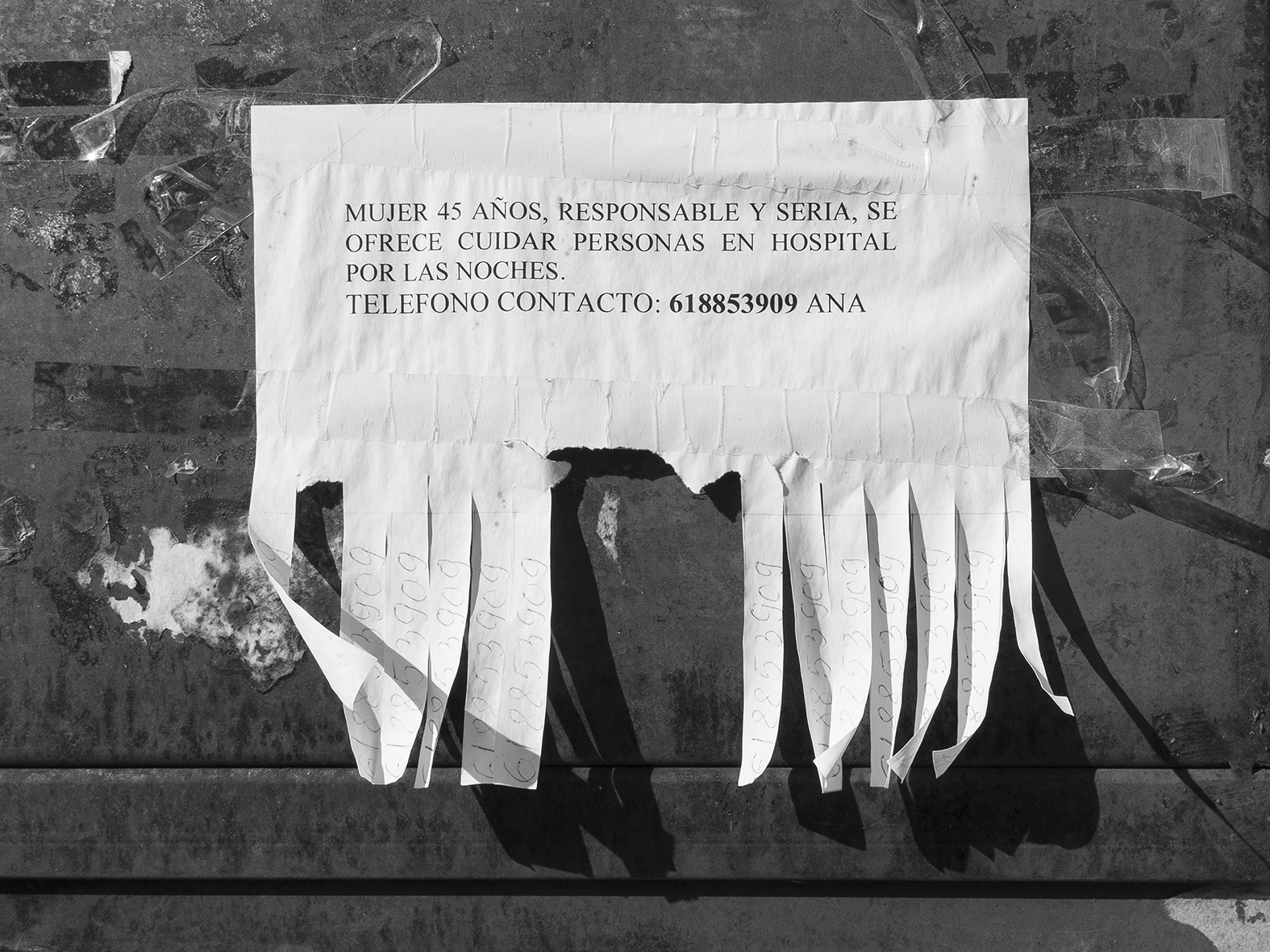

Anuncio colocado cerca del Hospital Virgen de la Salud. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Barrio de Palomarejos. Toledo.

Advertisement located near the Hospital Virgen de la Salud. In the vicinity of “Corea”. Palomarejos neighbourhood. Toledo.

"45-year-old woman, responsible and serious, available to take care of people in the hospital at night"

"45-year-old woman, responsible and serious, available to take care of people in the hospital at night"

Tienda de ultramarinos Celso. En el único comercio de la barriada fue común, durante los años que sucedieron a la construcción de las casas, la compra al fiado. El establecimiento era el lugar en el que los vecinos del barrio podían abastecerse incluso cuando no podían hacerlo en ningún otro sitio. Grupo de viviendas Pardo de Santayana (gobernador civil en 1953), «Corea». Barrio de Labañou. La Coruña.

Celso grocery shop. In the only shop open in the neighbourhood after the dwellings had been built, purchases were often made on credit. This establishment was the place where the residents wereable to get their provisions even when they were not able to do so anywhere else. Pardo de Santayana (Civil Governor in 1953) housing estate, “Corea”, Labañou neighbourhood, La Coruña.

Patio trasero de una vivienda lindando con la antigua carretera de Asturias. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Barriada de Cantamilanos. León.

Rear patio of a home adjoining the old road to Asturias. In the vicinity of “Corea”, Cantamilanos neighbourhood, León.

Corral autoconstruido y adosado al bloque. Un ejemplo común de construcción informal en la zona que, sin embargo, fue obviado por el plan de rehabilitación proyectado para la barriada. Grupo de viviendas Generalísimo Franco, «Corea». Barrio del Camp Redó. Palma de Mallorca.

DIY pen adjoining the block. A common example of informal construction in the area which, however, was overlooked by the rehabilitation plan. Generalísimo Franco housing estate, "Corea". Camp Redó neighbourhoob. Palma de Mallorca.

Palma de Mallorca, 2 de enero de 2012

Palma de Mallorca, 2 de enero de 2012

( Palma de Mallorca. January 2, 2012 )

Esta mañana se ha puesto en marcha el derribo del Bloque XIII, el segundo bloque en ser demolido en el grupo de viviendas del Generalísimo Franco, «Corea». La demolición tardará en completarse tres días. Parte de los escombros serán utilizados para rellenar la explanada, que acabará como un solar polvoriento o, en palabras del arquitecto encargado de la obra, como un «espacio abierto disponible para el uso de los residentes». Finalmente no se construirá, como estaba previsto para esta parcela en el plan de rehabilitación impulsado por el anterior equipo municipal, el aparcamiento subterráneo. Tampoco el centro de día ni las viviendas para ancianos, el casal de infancia y juventud o los apartamentos para jóvenes. Esta vez el viejo bloque no será reemplazado por uno nuevo como sucedió con el XII. El cambio de ejecutivo en las últimas elecciones municipales de 2011 ha traído consigo un cambio en la política de urbanismo. (...) En palabras del nuevo alcalde, Mateu Isern, el proyecto de rehabilitación estaba «condenado irreversiblemente al fracaso por estar estructurado como un gueto».

(...) La barriada de «Corea» cuenta con 568 viviendas de las cuales 20, oficialmente en desuso, son propiedad del consistorio; se estima que diferentes entidades bancarias acumulan 13 pisos vacíos, producto de desahucios, que no figuran en sus catálogos de oferta de vivienda; pueden, además, encontrarse múltiples pisos vacíos en manos de particulares, en su mayoría recibidos como herencia, consecuencia del «modelo Arrese» de promoción de vivienda social recalificable, en el que la propiedad pasaba de la autoridad estatal competente al inquilino beneficiario. La situación de abandono de los pisos, sumada a la negativa de ofrecerlos en alquiler social, ha favorecido situaciones de subarriendo informal, previa ocupación, de los apartamentos. Situaciones que han llevado a casos de coacción cuando los inquilinos, en su mayoría personas migrantes, dejan de pagar al descubrir a los falsos propietarios. La actividad laboral de estas personas suele ser también informal (recogida de chatarra, venta ambulante, narcomenudeo), en el mejor de los casos, producto del autoempleo. El valor en el mercado informal de un piso insalubre de 50 m2, en un entorno social y arquitectónicamente degradado, es de 250 euros mensuales.

(...) La barriada de «Corea» cuenta con 568 viviendas de las cuales 20, oficialmente en desuso, son propiedad del consistorio; se estima que diferentes entidades bancarias acumulan 13 pisos vacíos, producto de desahucios, que no figuran en sus catálogos de oferta de vivienda; pueden, además, encontrarse múltiples pisos vacíos en manos de particulares, en su mayoría recibidos como herencia, consecuencia del «modelo Arrese» de promoción de vivienda social recalificable, en el que la propiedad pasaba de la autoridad estatal competente al inquilino beneficiario. La situación de abandono de los pisos, sumada a la negativa de ofrecerlos en alquiler social, ha favorecido situaciones de subarriendo informal, previa ocupación, de los apartamentos. Situaciones que han llevado a casos de coacción cuando los inquilinos, en su mayoría personas migrantes, dejan de pagar al descubrir a los falsos propietarios. La actividad laboral de estas personas suele ser también informal (recogida de chatarra, venta ambulante, narcomenudeo), en el mejor de los casos, producto del autoempleo. El valor en el mercado informal de un piso insalubre de 50 m2, en un entorno social y arquitectónicamente degradado, es de 250 euros mensuales.

This morning the demolition of Bloque XIII has begun, the second block to be knocked down in the Generalísimo Franco housing estate, “Corea”. It will take three whole days. Some of the rubble will be used to fill in the esplanade, which will end up as a dusty plot, or, in the words of the architect in charge, as “an open space for residents’ use”. In the end they are not going to build an underground car park, as destined for this piece of land in the previous municipal council’s rehabilitation plan. Nor the day centre, nor the old people’s homes, the youth club or the flats for young people. This time the old block will not be replaced by a new one as happened with number XII. The change of government in the last municipal elections in 2011 brought a change in urban policy. (...) In the words of the new Mayor, Mateu Isern, the rehabilitation project is “doomed irreversibly to fail as it is structured like a ghetto”.

(...) The Generalísimo Franco estate, the “Corea” neighbourhood, has 568 homes of which 20, officially unused, belong to the city council; it is estimated that various banks between them have 13 empty flats, the result of evictions, that do not appear in their listings of homes for sale; you may also find a lot of empty flats privately owned, mostly inherited, a consequence of the “Arrese model” promoting social housing with a new category, in which the property passed from the relevant state authority to the benefitting tenant. The situation of abandoning flats, together with the refusal to make them available as social housing, has led to unofficial sub-letting of the apartments. Situations like this have led to cases of coercion when the tenants, mostly immigrants, stop paying when they discover they are not the real owners. The work situation of these people tends to be unofficial (collecting scrap, street vending, small-scale drug dealing) at best, the product of self-employment. The value of a sordid 50 m2 flat on the unofficial market, in a run-down environment socially and architecturally, is 250 euros per month.

(...) The Generalísimo Franco estate, the “Corea” neighbourhood, has 568 homes of which 20, officially unused, belong to the city council; it is estimated that various banks between them have 13 empty flats, the result of evictions, that do not appear in their listings of homes for sale; you may also find a lot of empty flats privately owned, mostly inherited, a consequence of the “Arrese model” promoting social housing with a new category, in which the property passed from the relevant state authority to the benefitting tenant. The situation of abandoning flats, together with the refusal to make them available as social housing, has led to unofficial sub-letting of the apartments. Situations like this have led to cases of coercion when the tenants, mostly immigrants, stop paying when they discover they are not the real owners. The work situation of these people tends to be unofficial (collecting scrap, street vending, small-scale drug dealing) at best, the product of self-employment. The value of a sordid 50 m2 flat on the unofficial market, in a run-down environment socially and architecturally, is 250 euros per month.

Pocos años después de su cancelación (en 2012), la maqueta del proyecto de rehabilitación de las viviendas del Generalísimo Franco, «Corea», en las oficinas del Consorci Riba, empresa pública encargada de su gestión. Barrio del Camp Redó. Palma de Mallorca.

A few years after its cancellation (in 2012), the model of the rehabilitation plan for the Generalísimo Franco housing estate, "Corea", in the offices of Consorci Riba, a state-owned company in charge of its management. Camp Redó neighbourhood. Palma de Mallorca.

Bloques sobre los que se proyectó el plan de rehabilitación, finalmente abandonado, en el grupo de viviendas Generalísimo Franco, «Corea». Al fondo, el Bloque XII, el único de los veintiséis que llegó a ser reformado. Barrio del Camp Redó. Palma de Mallorca.

A rehabilitation plan drawn up for these blocks in the Generalísimo Franco estate, “Corea”, was finally dropped. In the background, Bloque XII, the only block out of twenty-six that was ever renovated. Camp Redó neighbourhood, Palma de Mallorca.

Una cooperativa de vivienda obrera. Inmediaciones de «Corea». Barrio de San Juanillo. Palencia.

A workers' housing cooperative. In the vicinity of "Corea". San Juanillo neighbourhood. Palencia.

Vista de una calle en el barrio del Parpetuo Socorro, Huesca. Publicado por la Asociación de Vecinos en el Manifiesto por el desarrollo del barrio en marzo de 1979.

A street of the Perpetuo Socorro neighbourhood, Huesca. Published on the Neighbours Association manifesto for the improvement of the area in March 1979.

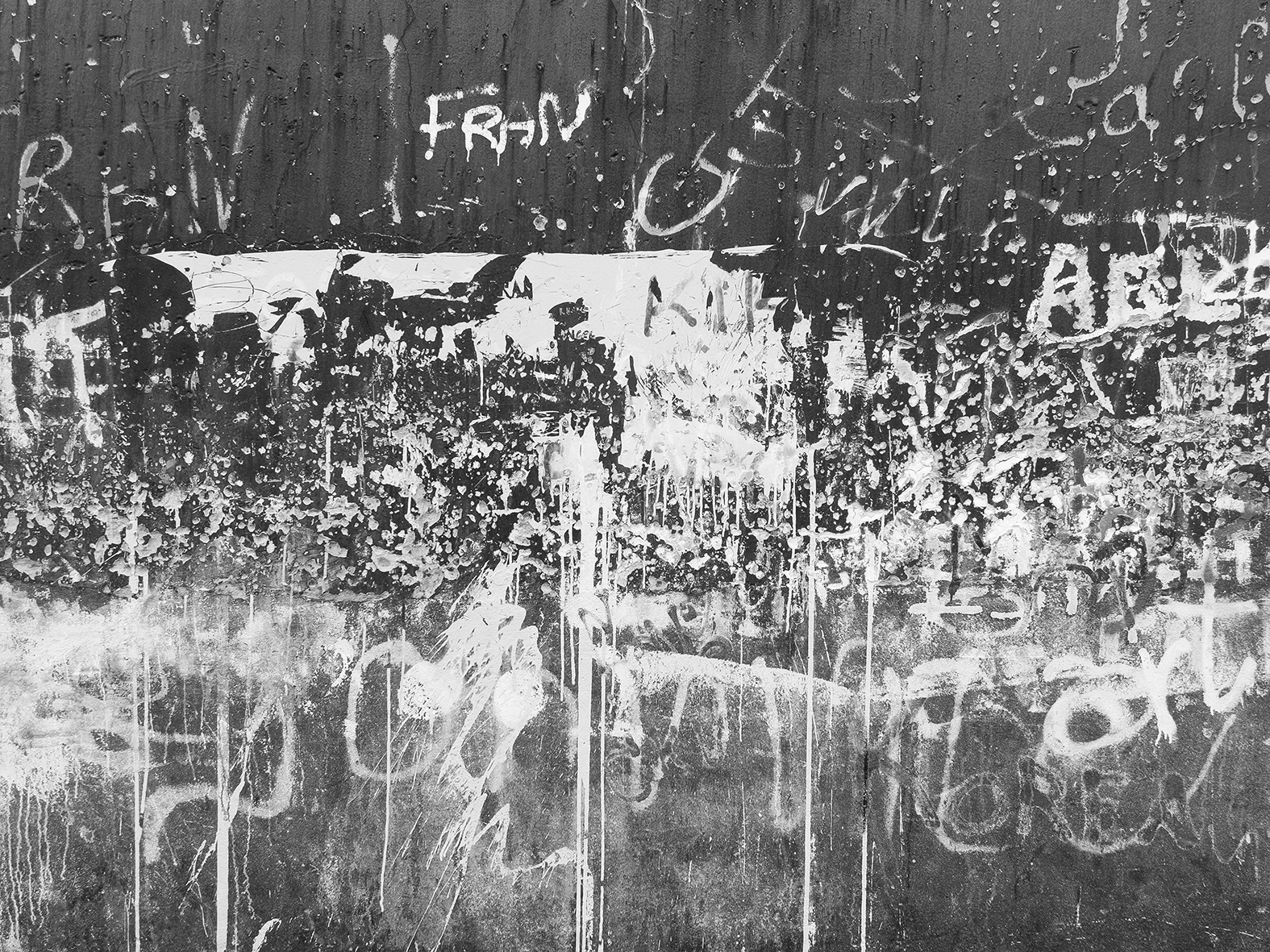

Detalle de una tapia. Grupo Pardo de Santayana (Gobernador Civil en 1953), «Corea». Barrio de Labañou. La Coruña.

Detail of a wall. Pardo de Santayana (Civil Governor in 1953) housing estate, "Corea". Labañou neighbourhood. La Coruña.

La Coruña, 4 de abril de 1953

La Coruña, 4 de abril de 1953

( La Coruña. April 4, 1953 )

José Manuel Pardo de Santayana, gobernador civil y ferviente falangista antiliberal, llega a la barriada acompañado por el camarada Tomás Romojaro, vicesecretario general del Movimiento, que ha venido desde Madrid para participar en el evento. Una banda de gaiteros marca la entrada de la Sección Femenina, del Frente de Juventudes y Sindicatos, de autoridades civiles y militares, del alcalde Alfonso Molina y del arquitecto Juan González Cebrián. El Padre Gil administrará el bautismo, la primera comunión y el matrimonio a una pareja que llevaba años haciendo vida marital sin la bendición de la Iglesia. Por sus servicios espirituales, una plaza llevará su nombre. Los vecinos alzan una pancarta: «Gracias, señor gobernador, por darnos unas viviendas sanas». El gobernador contesta con palabras de Franco: «Un hogar digno para cada español». Acepta el honor de dar su nombre al grupo de ochenta viviendas. Exaltado, promete apadrinar al primer niño que nazca en el nuevo poblado. Será una niña. La construcción se ha financiado con la venta de un excedente acumulado de aceite y azúcar, artículos racionados. Cada despensa ha sido bien provista. Ochenta familias han dejado de vivir en cobertizos con los animales, como los animales.

José Manuel Pardo de Santayana, Civil Governor and fervent anti-liberal Falangist, arrives in the neighbourhood accompanied by comrade Tomás Romojaro, general deputy secretary of the Movimiento 1, who has come from Madrid to take part in the event. A band of bag-pipers played as the Sección Femenina 2 entered along with the Frente de Juventudes y Sindicatos 3, civil and military authorities, the Mayor Alfonso Molina and the architect Juan González Cebrián. Padre Gil would administer the Baptism, the First Communion and marriage of a couple who had been living as man and wife for years without the Church’s blessing. A square would be given his name to record his spiritual services. The neighbours held up a sign saying: “Thank you, Governor, for giving us wholesome homes”. The Governor answered with Franco’s words: “A decent home for every Spaniard”. He accepts the honour of his name being given to the group of eighty homes. Elated, he promises to sponsor the first child to be born in the new neighbourhood. It will be a girl. The construction has been financed by the sales of an accumulated excess of oil and sugar, rationed goods. Every larder has been well supplied. Eighty families are no longer living in sheds with the animals and like the animals.

1. The Falangist Movement.

2. Female Section.

3. Youth and Syndicalist Front.

1. The Falangist Movement.

2. Female Section.

3. Youth and Syndicalist Front.

El ensanche de Los Rosales, desarrollo urbano de la década de 1990, visto desde el grupo Pardo de Santayana (gobernador civil en 1953), «Corea». Barrio de Labañou. La Coruña.

Los Rosales expansion district, an urban development from the nineties, seen from the Pardo de Santayana (Civil Governor in 1953) housing estate, “Corea”. Labañou neighbourhood, La Coruña.

Comedor social en la parroquia del Perpetuo Socorro. Grupo Pardo de Santayana, «Corea». Barrio de Labañou. La Coruña.

Soup kitchen in the Perpetuo Socorro parish. Pardo de Santayana estate, “Corea”. Labañou neighbourhood, La Coruña.

La Coruña, 3 de septiembre de 2014

La Coruña, 3 de septiembre de 2014

( La Coruña. September 3, 2014 )